The best movie posters are not necessarily the most aesthetically pleasing, but those that provoke the imagination of the spectator, turning them into storytellers in their own minds as they begin to wonder about the cinematic potential contained within the artwork.

When it was announced in 2009 that Ridley Scott would return to the Alien franchise to direct a prequel, excitement spread quickly. Following Aliens (1986), the series had steadily declined, Alien³ (1992) was famously disowned by its own director, David Fincher, and Alien: Resurrection (1997) effectively brought the franchise to a halt (if we discount the Alien vs. Predator spin-offs). The return of the filmmaker who birthed this universe carried enormous promise.

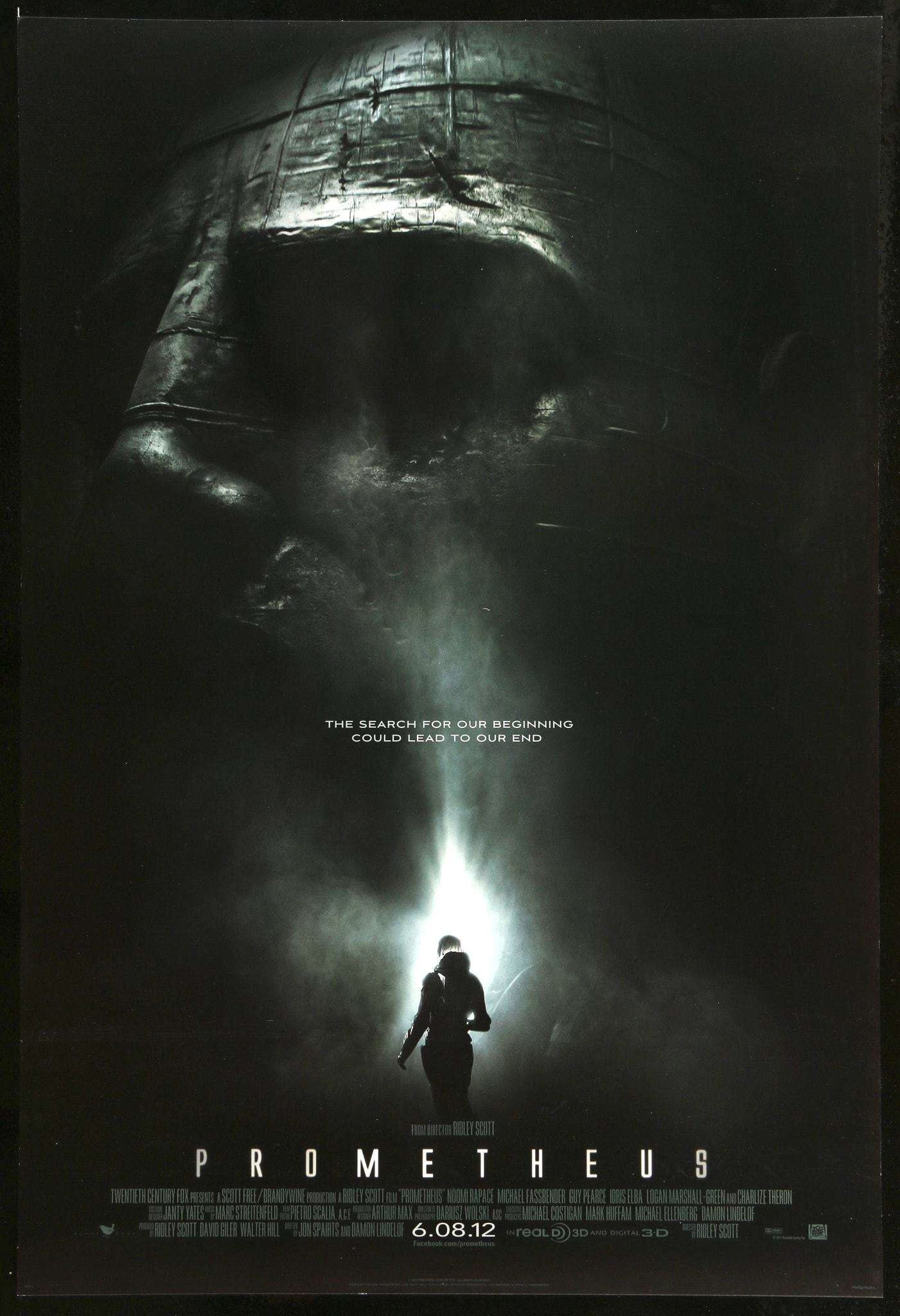

That anticipation deepened when the film was revealed to be titled Prometheus, a name strikingly unfamiliar within the franchise. Scott and writer Damon Lindelof were careful to insist that the film existed within the Alien universe, yet was not a direct prequel to the 1979 original. Suspicion grew. But when the poster was finally unveiled, optimism surged. Familiarity remained with certain design choices, yet it was overshadowed by the presence of the unknown. There were no eggs, no xenomorphs, no Ripley. Instead, the artwork offered something recognisable yet alien, provoking a powerful new sense of wonder. What elements within its design sparked such intense speculation?

How it provokes the imagination

The title font immediately recalls what featured in the poster of Aliens: thin, tall, compressed, yet still spaced enough to evoke isolation with the tightness introducing a feeling of claustrophobia. But then our attention quickly switches from the familiar to the unfamiliar.

Dominating the poster is a colossal stone head, illuminated by an eerie glow. The light suggests that something lies concealed beyond the artwork, a discovery awaiting the lone human figure standing before it. But unlike the glowing crack in the egg from the Alien (1979) poster that creates the same observation, there is nothing to suggest that this discovery may be a potential biological threat. We are left with questions. Who built this monument? Is it the work of the “people” who resemble it, or something else entirely?

Above the image sits the tagline: “The search for our beginning could lead to our end.” Its wording suggets that this search implicates us directly: our end. Could whatever lies beyond this discovery threaten humanity itself? What does “our beginning” even mean? Are we searching for our creators? Our gods? And if so, would we welcome what we find? The monument resembles a human face, a nose, brow, eye sockets, ears, yet it is unmistakably lifeless. But are we certain this head is merely a monument? Could it be something more?

Near the human figure stands an ambiguous, oval-shaped object, solid and stone-like, tilted unnaturally. It does not resemble an egg. Is it part of the environment? A pod? A vessel? Is anything contained within it? The poster refuses to clarify.

What becomes clear is scale. The human presence is insignificant against the vastness of the head. Whatever this structure represents, it feels greater and far more powerful than us. The poster suggests not survival horror, but something deeper, a confrontation with origin, purpose, and insignificance. We’re no longer dealing with a regular Alien film.

So… Is the film as good as the poster?

Upon release, Prometheus divided audiences, particularly those hoping for clear answers regarding the origins of the xenomorph and the Space Jockey from Alien (1979). The film did not explain how the derelict ship ended up on LV-426, nor did it provide a definitive account of the eggs it carried. Instead, it offered fragments: the Engineers, suggestions of genetic creation, and disturbing imagery carved into ancient stone walls.

For many, this felt unsatisfying. But this refusal to explain everything is precisely what allows the film to succeed. Rather than laying out a clear path toward the events of Alien, Prometheus leaves that connection open, encouraging speculation about how these discoveries eventually lead to the events of the 1979 film.

Like the poster, the film leaves us with ideas rather than conclusions. Why did the Engineers create us? Why did they later seek to destroy us? What did they find lacking in their creation? And what consequences might follow from discovering the truth about our origins? These questions linger long after the film ends, expanding the sense of wonder rather than closing it down.

What Prometheus offers is something far more philosophical than many expected from the franchise. It turns the attention toward creation, faith, and consequence. The fascination it leaves behind is not stronger than that of the earlier films, nor does it replace it, it’s just a different focus. Prometheus confronts us with the unsettling idea that understanding where we come from may be more disturbing than never knowing at all.